The Agenda and Dilemmas of Constitutional Reform in Bangladesh

by M Jashim Ali Chowdhury, 18 November 2024

Idea International, Constitutionnet, Voices from the Field Report

After protests that led to the fall of an authoritarian government, Bangladesh’s current interim government has established ten reform commissions, including one on the constitution. The Constitution Reform Commission faces the daunting challenge of setting an agenda while navigating multiple dilemmas of mandate, inclusivity and sustainability. The country’s constitution has already experienced a rollercoaster ride through various amendments, and its ideological pillars—democracy, socialism, secularism, and nationalism—have been intensely contested. Further, the parliamentary structure of government has enabled a form of prime ministerial dictatorship, while the country’s political parties have remained non-democratic and temperamentally authoritarian, with little sign of willingness to evolve. How the Commission addresses these issues will be critical as Bangladesh faces another defining moment in its constitutional journey – writes M Jashim Ali Chowdhury

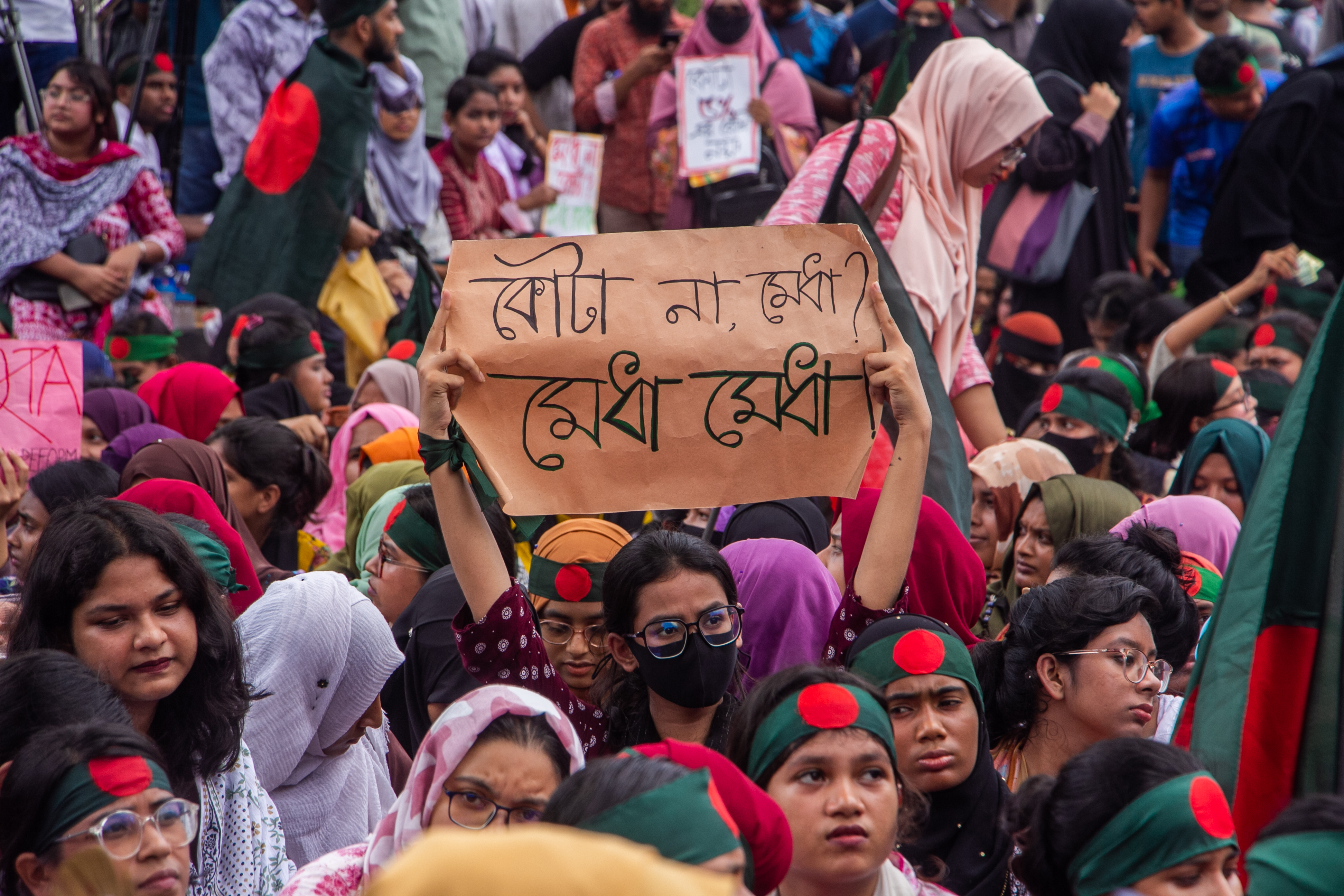

Quota reform protest in Bangladesh with a sign reading "Not quotas, merit!"

(photo credit: Rayhan9d via Wikimedia Commons)

Introduction

Bangladesh’s constitutional journey has been a tumultuous one, marked by profound ideological shifts, political upheavals, and a series of amendments that have both shaped and distorted its foundational principles. Since gaining independence in 1971, the country has grappled with defining its constitutional identity amid extreme political contestation.

The 1972 Bangladesh Constitution — celebrated by some as ‘the best and most eloquent instance of . . . [the people’s] self-expression as a nation’ — adopted a Westminster parliamentary system. It was based on four foundational pillars of nationalism, secularism, democracy and socialism. However, in 1975, it was radically transformed into a national party-led presidential system, soon to be overthrown by a coup leading to military rule. Subsequent military regimes amended the constitution drastically, re-introducing multi-party politics but retaining the presidential system, removing references to socialism and secularism, and shifting from Bangalee nationalism—which emphasized the Bengali ethnic and linguistic identity—towards a Bangladeshi nationalism and Islamic values. In 1982, another military coup led to the reimposition of martial law. Though parliamentary democracy was restored in 1991, it failed to stabilize the political landscape due to mutual distrust among the ruling and opposition parties, suppression of intra-party dissent and parliamentary opposition, violent street agitation, election rigging, and back-door conspiracies for ascending or clinging to power, which eventually became the norm.

The introduction of a non-party caretaker government system in 1996 aimed to ensure fair elections. However, it was later manipulated and ultimately repealed in 2011, leading to legitimacy crises in subsequent elections marred by allegations of misconduct. In 2024, widespread protests—initially sparked by demands for reform of civil service quotas— culminated in the fall of the authoritarian Awami League (AL) government.

An “interim” government, endorsed by protest leaders, first established six reform commissions focusing on the judiciary, bureaucracy, police, electoral system, anti-corruption, and most prominently, the constitution. Later, the government formed four more reform commissions on health care, mass media, and labour and women’s rights. Among the ten commissions, the Constitutional Reform Commission faces the most significant dilemmas stemming from Bangladesh’s decades-long political contestation around constitutional ideals and design. Central to these challenges is the ongoing battle around the constitutional ideals of secularism, socialism, and nationalism, which have perpetuated divisions within society. The Commission must also find a workable and sustainable balance in the constitutional design that has often been blamed for giving rise to authoritarianism.

What Reforms are on the Table?

Bangladesh’s Constitution of 1972 was modelled on a UK-style parliamentary system combined with a US-style “strong form” of judicial review that allows the Supreme Court to test the constitutionality of legislation. The President acts as a ceremonial head of state bound by the Prime Minister’s advice. The Prime Minister, the leader of the majority party, is accountable to the parliament. However, a paradoxical provision—Article 70—forces MPs to vote strictly on the party line or lose their parliamentary seats. Though the framers of the Constitution defended it as a stabilising measure against the frequent fall of governments, the provision has allegedly taken partisan whipping to an extreme level, paving the way for a prime ministerial dictatorship. Though the judicial branch has been granted substantial independence in the Constitution, the Supreme Court of Bangladesh has been severely politicised, while the subordinate courts are controlled by the executive branch. The Election Commission and other integrity institutions have also been subordinated to the government.

During the civil service quota reform movement, the student protesters had no other reform agenda. Most of the reform demands were voiced by civil society groups calling for transparency, accountability and orderly transfer of powers during the AL regime’s sixteen-year-long rule. After the fall of the AL government on 5 August 2024, student protesters accelerated their push for constitutional reform. Alongside calls for adopting an entirely new constitution, there are proposals for reducing the prime minister’s powers and balancing them with those of the president, term limits for the prime minister, establishing a bicameral legislature, and even changing the parliamentary system to presidential.

Currently, AL, arguably the country’s largest political party, is not expected—and perhaps not welcome—to submit any proposal. The second of the Big Two—the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)—published a 31-point reform agenda in 2023, which resonates with issues such as depoliticizing appointments in the higher judiciary, election commission, and other accountability institutions; creating a bicameral legislature; introducing a two-term limit for the prime minister; restoring the election-time caretaker government; and reviving Bangladeshi nationalism. The Jamaat Islami (JI), the third-largest party and arguably the chief beneficiary of this regime change, has come out with its own 10-point reform proposal, including a shift to a proportional representation (PR) system rather than the current first-past-the-post (FPTP) system. It has been argued that the PR system may ensure fairer and more credible representation in the parliament and government, as the FPTP system often disproportionately benefits the Big Two—AL and BNP. Interestingly the JI has remained silent about the fate of the foundational pillars of the Constitution, particularly secularism.

"Parties being the chief constitutional actors, any constitutional reform that does not require the political parties to be internally democratic is likely to fall flat . . ."

The BNP and JI’s reform proposals are also silent on the daunting task of professionalizing the bureaucracy and making it accountable to the legislature. Another conspicuous omission in the conversation is internal reform within the political parties themselves. Parties being the chief constitutional actors, any constitutional reform that does not require the political parties to be internally democratic is likely to fall flat once the patriarchal party leaders take the reins of power in the future. In the past, Bangladeshi political parties have almost universally abused their constitutional amendment powers for their partisan and coterie interests.

The Dilemmas

The Constitution Reform Commission faces at least four major dilemmas. The first one is whether to reform the existing constitution or adopt a new one. As Professor Ngoc Son Bui outlines, arguments to replace a constitution may stem more from ideological inclination than a genuine need for structural realignment. Understandably, the student protest leaders' enthusiasm for replacing the 1972 Constitution appears to arise from their doubts about its foundational principles. If the student leaders’ zeal for constitutional replacement is acted upon, it will surely reopen the old wounds of the ideological battle. Despite the AL’s fall, there remains deep societal reverence for the liberation war and its ideals. Currently, there are no serious demands from the political parties to write a new constitution. Instead, opposition to the idea of constitutional replacement and the demand for transferring power to the people’s elected representatives are growing. It appears that the opportunity cost of making a new constitution could be higher than the protest leaders anticipate. Unchained from over 50 years of Bangladesh Supreme Court constitutional jurisprudence, a new constitution will risk further replacement, particularly if the AL comes back to power, which is not at all impossible. Opening the door to frequent constitutional replacements may make the foundation of constitutionalism shaky—particularly risky for societies as divided as Bangladesh.

"As seen in 1972, excluding the Islamist and conservative forces from the constitution-making process left a deep participation gap, undermining the constitution’s longer-term endurance."

The second challenge for the Commission centers on participation and inclusivity, again originating from the ousted AL regime and its huge social base. How can the Commission achieve a reform acceptable to all while simply ignoring the AL? As seen in 1972, excluding the Islamist and conservative forces from the constitution-making process left a deep participation gap, undermining the constitution’s longer-term endurance. Ironically, the same seems to be the case this time. A relatively pragmatic approach could be to show ‘an optimal level of constitutional deference’ to ideologically contested issues and focus on the 1972 Constitution's design flaws only. However, there are signs that the student leaders might not be interested in this. Therefore, the reform initiative carries a visible Achilles’ heel.

The third question for the Commission is how to materialise the reforms. There is a perception that the Commission’s eight members—primarily practicing lawyers and legal academics connected with a single Bangladeshi university, the University of Dhaka—and the chairperson, who is on deputation from a U.S. university, lack the representativeness needed to dictate something as significant as the constitution of a country. Considering that the 1972 Constitution was drafted and adopted by a democratically elected 469-member Constituent Assembly, a strong argument can be made that this reform commission does not have the democratic mandate to replace or amend it. It has been proposed that any constitutional reform or replacement in Bangladesh must be pursued through democratic and participatory processes such as a constituent assembly, elected parliament or referendum. Although the interim government has declared that it will take the Commission’s proposals to the political parties (excluding the AL and its allies) and consult them before finalising the reform packages, it is not clear when and how the reform will be executed. The BNP has demanded that the Commission simply prepare a set of recommendations and leave the reforms to an elected parliament. While this strategy might facilitate some sort of political compromise between the parties, the student protesters and the interim government do not seem to be very enthusiastic about this idea. Moreover, uncertainty persists over which political parties or coalitions may come to power through the next election and how the interim government would negotiate with them. The most uncertain is the tenure of the interim government and when the election would be held.

"[T]here are some legitimate questions looming around the interim government’s own commitment to the reforms that it advocates . . ."

Fourthly, there are some legitimate questions looming around the interim government’s own commitment to the reforms that it advocates. Pending the work and recommendations of the reform commissions on the judiciary, electoral system, anti-corruption, police, public administration, and mass media, the government has sent some acting Supreme Court judges into forced leave and appointed new ones seemingly for political reasons, constituted a Search Committee under an AL-made law for appointing a new Election Commission, dismissed trainee police officers in controversial ways, forced the entire public service commission and anti-corruption commission to resign and reconstituted those with individuals of its own choosing. The government’s decision to cancel the accreditation of around sixty journalists has drawn protest from international press freedom bodies. All these actions raise critical questions about the government’s sincerity regarding its reform commitments and could potentially shake the moral base of those reforms in future.

Conclusion

Bangladesh is one of the world’s busiest laboratories of constitutional experiments. Fifty-three years into its constitutional beginning, the country has seen different types of governments: parliamentary government with one-party dominance (1972-75), a one-party presidential government (1975), rule by several military governments (1975-90), several election-time non-party caretaker governments (1991, 1996 and 2001), several parliamentary governments in a competitive multi-party system (1991-96, 1996-2001, 2001-06, 2009-13), a military-backed government (2007-08), a long stretch of one-party monopoly (2009-24) and currently, an extra-constitutional “interim” government (2024). The seemingly never-ending cycle of political instability illustrates how difficult the burdens of the Constitutional Reform Commission are—both in terms of its mandate and the sustainability of its efforts. The Commission must navigate these historical wounds, balance its seemingly ominous reform agenda, and overcome the dilemmas if it is to forge a path toward a more stable and inclusive constitutional order. With the critical challenges identified above, only the future can answer what it brings and how it sustains.

M Jashim Ali Chowdhury PhD is Lecturer in Law at the University of Hull, United Kingdom.

♦ ♦ ♦

Suggested citation: M Jashim Ali Chowdhury, ‘The Agenda and Dilemmas of Constitutional Reform in Bangladesh’, ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, 18 November 2024, https://constitutionnet.org/news/voices/agenda-and-dilemmas-constitutional-reform-bangladesh